AERO VINTAGE BOOKS

History of B-17E and XC-108A Desert Rat

(Happily adapted from material in Final Cut: The Post-War B-17 Flying Fortress.

B-17E s/n 41-2595 was the 203rd B-17E built by Boeing at Seattle, and was delivered to the AAF on April 14, 1942. It was immediately placed into the training role, being first assigned to the 97th Bomb Group at MacDill Field, near Tampa, Florida. The 97th BG had been activated on February 3, 1942, at MacDill, so 41-2595 was one of the early assigned aircraft. The new group moved to Sarasota AAF, Florida, the following month, and 41-2595 followed along. The 97th went overseas in May (and flew the first 8th Air Force mission three months later), whie 41-2595 was reassigned to MacDill for continued assignment to training. In September 1942 it was reassigned to another major B-17 bomber training base, Walla Walla, Washington. It spent the next nine months assigned to various B-17 training bases, ending at Ainsworth AAF, Nebraska, in February 1943. In March 1943, it was assigned to Wright Field at Dayton, Ohio, and evidently used as a transport. In August 1943 it was assigned to the XC-108 program.

The C-108 designation was initially assigned to various transport conversions of the B-17. The designation was made when the AAF was applying new designations for modifiied aircraft instead of applying a type prefix, the CB-17 being used later. The C-109 designation was similarly applied to B-24 modifications. For the C-108, there was no particular standard. There were a total of four B-17s designated as C-108s: the XC-108 was sistership s/n 41-2593 modified by Boeing for use as a transport for Gen. Douglas MacArthur, it becoming the first of several Bataans. The YC-108 was s/n 42-6036 and was modified with a VIP interior and used in India. The XC-108B was s/n 42-30190, and was used to test the use of the B-17 design as a fuel tanker. Finally, the XC-108A, s/n 41-2595, was a modification to determine the suitability of the B-17 design for use as a transport. Whereas the modification work for the XC-108 (for MacArthur) was done by Boeing, the other three were done by the Fairfield Air Service Command at Patterson Field, Ohio.

41-2595 was brought into the C-108 program on August 17, 1943, becoming the XC-108A in a conversion completed by March 1944. The primary modifications all centered on making the Fortress into a standard transport type capable of carrying troops, large cargo, or injured personnel in a evacuation capacity. Armor and armament was stripped from the bomber. The interior arrangement was reworked, with the radio operator and navigator moving into the cockpit behind the pilots where the top turret had once been positioned. The nose compartment was rebuilt to provide for cargo, litter, or troop transport, access being gained by either the crawlway under the cockpit or a solid, hinged nose piece that replaced the built-up frame and glass assembly of a standard B-17E. The bomb-bay doors were sealed and the bulkhead between the bomb-bay and what had been the radio-compartment was opened up. The bulkhead between the radio compartment and the waist area was removed. Provisions for litters, cargo, or troop-transport were installed in both the former bomb-bay and the aft fuselage. A large, upward-hinging cargo door was installed in the left waist position to ease loading and unloading operations. After initial testing was completed at Wright Field, the XC-108A was slated for an operational test in India ferrying men and equipment over the Hump into China. Though deemed ready for service in early March 1944, 41-2595 would develop continual engine problems that apparently plagued it through its entire test period. Whether this was primarily due to the state of the engines on the airframe, or the different operating conditions required by the airplane’s new mission is open to question, but things started off poorly when initial engine difficulties required a week delay in the aircraft’s departure as required engine maintenance was performed.

In late March 1944 the airplane left for India, its planned ferry route taking it through the Caribbean to South America, across to Africa and northeastward to India. Carrying a four man ferry crew and two passengers, the plane loaded up in Miami for the hop to Puerto Rico but again developed engine difficulties. As the plane was in a test series, maintenance had to be coordinated through Wright Field that only slowed repairs. After stopping in Puerto Rico, the flight continued to Belém, Brazil. Four hours out of Belém, and over the jungles of northeastern Brazil, engine number three caught fire. The engine was shut down, but efforts to extinguish the fire were unsuccessful and it continued to smolder. The pilot gave permission to anyone who wanted to bail out, but the foreboding jungle no doubt gave everyone second thoughts about that option, and all decided to stay with the C-108 as long as possible. The pilot nursed the plane to Belém and a successful landing, with the crew chief and a passenger jumping from the plane with fire extinguishers as it rolled to a stop on the runway. Repairs took another week before the crew made the trans-Atlantic hop to the Ascension Islands, followed by a leg to Accra in present day Ghana. More engine difficulties ensued there, causing extensive delays and resulted in the ferry flight stretching to almost eight weeks.

Transcript of a letter from Col. Robert Bowman and his recollections of the XC-108A deployment

After finally arriving, the XC-108A was operationally based at Chabua in India, though details of its actual use are not available. One would suspect, however, that given the difficulties of the ferry flight and the altitudes involved in transporting material into China, the XC-108A was not successful. In any event, 41-2595 returned to the U.S. in October 1944 via the North Atlantic ferry route, arriving at Dow Field near Bangor, Maine, on October 18, 1944. The aircraft was assigned to the 1379th Base Unit and put to use as a transport. Flight operations were conducted to Greenland and Newfoundland, as well as throughout the northeastern U.S. The military record card indicates 41-2595 was later assigned to the 147th Base Unit and the Continental Air Force, but apparently its duties remained the same. One of the pilots assigned to fly s/n 41-2595 was Flight Officer Maurice F. Taylor, then assigned to the 1383rd AAF Base Unit at Goose Bay.

1988 letter from Maurice Taylor about him flying the XC-108A

AAF commendation to F/O Maurice Taylor about him flying the XC-108A

Excerpt from Maurice Taylor's logbook from October 1945

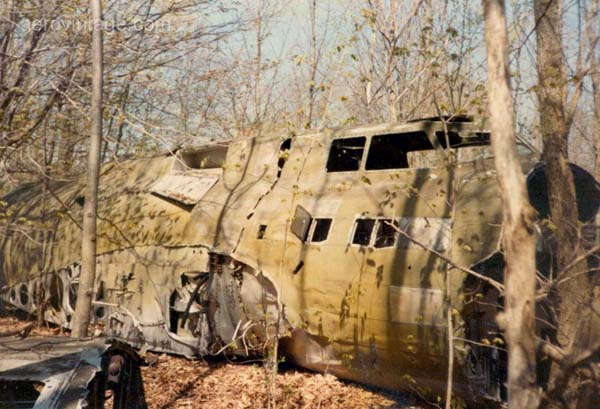

The last operational flight of XC-108A s/n 41-2595 was conducted in mid-December 1945 and it was subsequently authorized for salvage at Dow Field and thought to have been broken up for scrap. However, the story of 41-2595 does not end here. It would appear that the owner of an auto junk yard near Dow Field made a successful bid on 41-2595 for salvaging, as well as a B-25, a C-47, an O-47 Owl and who knows what else. He hauled his booty away to his junkyard and let his kids have at the old airplanes. The B-25 was cut up, drawn and quartered like a side of beef. The C-47 and O-47 suffered a similar fate. However, the B-17 was found too big and strong, and only suffered great gashes during initial efforts at disassembly. The nose was cut off forward of the cockpit and the tail section was cut into four pieces. The wings were damaged from the rear spar aft, and other parts suffered at the effort at scrapping. When the airplane was disassembled, the lower part of the cockpit section was crushed, as was the upper part of the nose section. The remains were then left to be swallowed up by an advancing forest of undergrowth and a receding memory.

The aircraft remained pretty well untouched until 1968. In that year a fellow restoring a B-25 in Massachusetts heard of the possibility of a B-25 airframe rotting in Maine. He and a crew of several men came looking for salvageable parts and found the XC-108 instead. The group was somewhat dismayed by the lack of a B-25, but decided to disassemble the B-17 and remove it instead. Without securing permission from anyone, they went ahead and de-mated the wings from the fuselage and then broke the fuselage into component parts. The engines, propellers, and landing gear were detached. As they began loading the material aboard the trucks, it was quickly determined that there was more airplane than available room. In the end, all that was taken were the engines, cowlings, landing gear, and propellers. The group disappeared into the sunset, but the components resurfaced in 1986 when an offer was made to the National Warplane Museum at Geneseo, New York, for the material in exchange for a few rides on the museum’s B-17, 44-83563. The museum donated the rides, but the supposed donor disappeared again into the sunset, and hasn’t been seen since.

The second discovery of the XC-108A remains was made by Steve Alex of Bangor, Maine. In 1985 Alex purchased the remains from the two sons of the original owner, who had since passed away. Alex knew that Mike Kellner, a thirty year old vintage aircraft buff from Marengo, Illinois, was intent on getting a hold of a B-17 for restoration, and promptly resold the Fortress to him for $7,250. Kellner faced the monumental task of gathering the various pieces of the historic plane from the overgrown woods, transporting them from Maine to his home in Illinois, and somehow amassing the financial and logistical means to reconstruct the bomber. On the first two items he has been successful. The entire airplane was moved to the local airport at Galt, Illinois, with all but the fuselage stored in enclosed trailers. The problems of restoring the bomber has obviously been a much tougher nut to crack. Beyond the obviously poor condition of the airframe and the lack of readily available parts for the B-17E, Kellner has had to establish financial backing and find some people with the technical expertise to pull the airplane together.

After several years of work at Galt, the airframe was moved in 1995 to Morengo, Illinois. There, Kellner has built a large building which allows most of the airplane to be kept indoors. Work has concentrated on the fuselage. Since the fuselage was cut in several spots the basic structure has required attention, with numerous longerons and stringers being repaired or replaced. The aluminum extrusion used for the longerons was not available so it has been custom manufactured. Many skin panels and other parts have also been hand built. Heat treating the parts had been a problem until a vendor was located in Oregon which could handle the complexity of the work. Each part of the restoration process has been inspected and documented to Federal Aviation Adminstration airworthiness standards to ensure the airplane can be properly certificated at the completion of the massive effort. Kellner has organized a group of volunteers to work on the airplane. Though work is slow, substantial progress has been made in the past decade. While stripping paint from the nose section, the name Desert Rat emerged from beneath a few layers of paint. It’s been assumed that the airplane was so dubbed during its use as a trainer at Walla Walla, Washington, in 1942.

In any event, the airplane will be restored to a B-17E configuration with turrets and other equipment reinstalled. The planned paint scheme will be the standard AAF olive drab and gray with early style insignia to replicate the airplane as it was originally delivered from Boeing. The name Desert Rat will be reapplied as nose markings. A time frame for the restoration isn’t set; each task is performed as resources allow. The effort continues as a privately funded restoration and always welcomes assistance, financial or otherwise. It would appear that the hard work of Kellner and his volunteers will put yet another B-17 back into the air.

Main Desert Rat Page

The Most Recent Update of the Restoration of B-17E 41-2595

The Restoration Log in Words and Photos

The History of Desert Rat (B-17E and XC-108A s/n 41-2595)

How You Can Help: Needs/Disposal/Contact Information, Etc.

Back to the Main Aero Vintage Page

Updated: